Biography

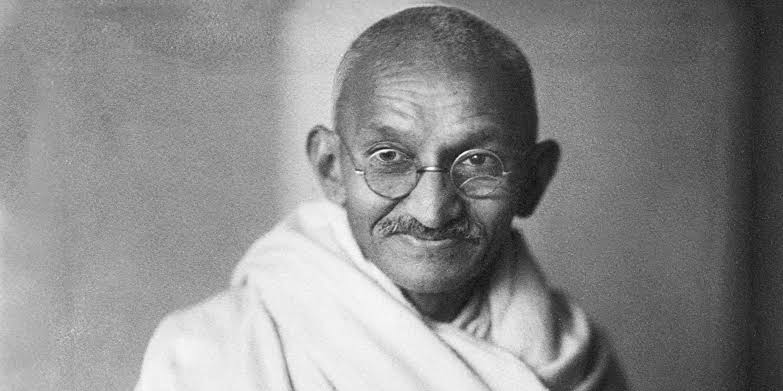

Mahatma Gandhi Biography (In English): Life, Wife, Death Date, History & Books

Mahatma Gandhi born Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in 1869 became the most recognizable face of nonviolent political struggle in the twentieth century.

Trained as a barrister in London, he developed a political ethic that relied not on the force of arms but on the force of conscience.

From community organizing in South Africa to nationwide campaigns in India, Gandhi’s method of satyagraha literally “truth-force” reframed resistance as a patient, public demonstration of truth, discipline, and sacrifice.

The strategy was audacious in its moral clarity and surprisingly pragmatic in effect: boycotts, marches, and civil disobedience eroded the legitimacy of British imperial rule while teaching millions how to act together without hatred.

| Full Name | Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi) |

| Age | 1869–1948 (died at 78) |

| Occupation | Lawyer, anti-colonial leader, political ethicist, writer |

| Net Worth | Gandhi embraced material simplicity and self-reliance |

| Family Background | Born in Porbandar, Gujarat, to Karamchand Gandhi (a regional chief minister) and Putlibai; raised in a Vaishnav household shaped by Jain ideas of nonviolence and self-discipline. |

| Partner/Wife | Kasturba (Kasturbai) Gandhi; married in 1883; she partnered in his activism and died in 1944. |

| Career Journey | Law studies in London → activism in South Africa (1893–1914) → return to India (1915) → Champaran and Kheda (1917–18) → Non‑Cooperation (1920–22) → Salt March (1930) → Civil Disobedience → Quit India (1942). |

| Leadership Style | Ahimsa (nonviolence) and satyagraha (truth-force); persuasion through personal example—fasts, spinning, simple living. |

| Key Achievements | Helped transform the Indian National Congress into a mass movement; broadened participation of women and rural citizens; global exemplar of nonviolent resistance. |

| Controversies | Debates around early South African writings on race, views on caste and celibacy; differing scholarly interpretations of his evolution and legacy. |

| Death Date | 30 January 1948 — assassinated in New Delhi by Nathuram Godse. |

| Legacy | Enduring influence on civil rights and pro-democracy movements worldwide; continuing study and critique in academia and public life. |

Image Source: Wikipedia

Early Life and Education

Gandhi was born on 2 October 1869 in Porbandar, a coastal town in present-day Gujarat. His father, Karamchand, served as a diwan an administrative chief in a local princely state.

His mother, Putlibai, embodied a devout religiosity marked by fasting, vows, and a quiet insistence on self-control. The syncretic environment of Gujarat Hindu Vaishnav traditions in dialogue with Jain teachings on nonviolence left a lasting imprint on the young Gandhi.

In 1888 Gandhi sailed to London to study law at the Inner Temple. The voyage itself was controversial in his community crossing the seas was frowned upon but he had the tacit support of family elders.

In England he experimented with diet reform, joined vegetarian societies, and read widely, encountering collections of religious and philosophical writing that would shape him: the Bhagavad Gita, the Sermon on the Mount, and works by Tolstoy and Ruskin.

He returned to India in 1891 as a qualified barrister, but a faltering start at legal practice soon sent him seeking opportunities elsewhere.

South Africa: The Laboratory of Satyagraha (1893–1914)

In 1893, Gandhi accepted a one-year contract with an Indian firm in Natal, South Africa a decision that turned into two decades of formative work. Confronted by racial discrimination on trains, in courtrooms, and in public life, he began organizing the Indian community.

The early campaigns focused on practical grievances pass laws, unjust taxes, marriage recognition but Gandhi’s response was more than legal petitioning. He crafted satyagraha as a disciplined public stance: insistence on truth, refusal to cooperate with unjust laws, acceptance of punishment without retaliation, and scrupulous transparency. Crucially, he asked resisters to prepare themselves morally: to avoid violence in word and deed, to keep promises, and to remain open to negotiation.

The South African years were a laboratory where Gandhi refined methods he would later bring to India: mass meetings, negotiated settlements, and strategic use of the press.

He also founded communes like the Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm to test a way of life built on simplicity, shared labor, and education that formed the character of resisters.

By 1914, Gandhi had established himself as a capable organizer and a moral experimenter, ready to return to India with a tested repertoire of tactics.

Return to India and the Making of a Mass Leader

Gandhi returned to India in 1915, taking time to travel, observe, and listen before assuming national leadership. Mentored by the moderate statesman Gopal Krishna Gokhale, he rejected a politics of elite petition and instead emphasized village reconstruction and constructive work hygiene, basic education, hand-spinning, and local industry as the backbone of national renewal.

Two early campaigns made his reputation. In Champaran (1917), he helped indigo cultivators challenge exploitative plantation contracts; in Kheda (1918), he supported peasants resisting revenue demands after crop failure.

These movements were locally grounded but nationally resonant: Gandhi framed them as moral arguments, encouraging negotiation while preparing for non-cooperation if talks failed.

The British, accustomed to either sporadic riots or elite negotiation, now faced a third force: disciplined crowds acting with self-restraint and public purpose.

Non-Cooperation and Civil Disobedience

From 1920 to 1922, Gandhi launched the Non-Cooperation Movement, urging Indians to boycott colonial schools, law courts, and goods.

He paired abstention with construction spinning khadi, building local schools, and promoting Hindu–Muslim unity.

The movement drew millions, transforming the Indian National Congress into a mass organization.

Violence at Chauri Chaura in 1922 led Gandhi to pause the campaign; he insisted that means mattered as much as ends.

The episode earned him critics who preferred continuous escalation, yet it also affirmed the central claim of his politics: the method shapes the society being built.

By 1930, the Salt March supplied a new symbol of resistance. Gandhi and a small band walked 240 miles to the coastal village of Dandi to make salt, defying the British monopoly.

The gesture, homely yet radical, invited ordinary people to take part in history with everyday acts.

Arrests followed, but the world’s press captured the contrast between a frail-looking leader and the empire’s machinery of rule.

Civil Disobedience continued in waves through the 1930s, punctuated by negotiations and prison terms that became part of Gandhi’s public pedagogy.

Quit India and the Challenge of War

During the Second World War, with Britain fighting for survival, Gandhi issued the 1942 “Quit India” call an uncompromising demand for immediate independence accompanied by the phrase “Do or Die.” The colonial state responded with mass arrests and censorship. Gandhi spent years in detention; his wife Kasturba died in prison in 1944.

The campaign’s short-term gains were limited, but it fixed the horizon of Indian politics: the British departure was no longer a question of if but when. Meanwhile, Gandhi struggled to keep communal tensions from overwhelming the national cause.

Philosophy and Personal Practice

Gandhi’s politics cannot be separated from his personal practice. He cultivated vows of truthfulness, nonviolence, simplicity, and chastity, believing that public authority begins with self-mastery.

Spinning khadi was not mere symbolism; it was a critique of exploitative industrialization and a call to economic self-reliance.

His fasts were designed to appeal to the conscience of both followers and opponents, dramatizing the moral stakes of political choices without inciting hatred. He insisted on transparency publishing accounts, answering critics, and acknowledging mistakes arguing that openness disciplines power.

Gandhi’s reading was ecumenical. He drew from the Bhagavad Gita a vision of selfless action, from Tolstoy an ethic of love, and from Thoreau the civil resister’s refusal to cooperate with injustice. He saw religion as a quest for truth rather than a badge of identity and tried often imperfectly to build bridges across India’s religious communities.

His ashrams served as moral schools where residents practiced equality across lines of caste and gender, even as the larger society struggled to accept those ideals.

Debates and Critiques

No account of Gandhi is complete without acknowledging debate. Scholars scrutinize his early writings in South Africa for racial hierarchies common to his time and challenge his prescriptions on caste and sexuality.

Feminist critics question aspects of his experiments with celibacy; Dalit thinkers fault him for not dismantling caste with sufficient urgency.

Supporters respond that his views evolved significantly and that his public program widened participation for groups previously marginalized in politics.

The point is not to settle the debates but to understand Gandhi as a figure whose legacy invites continuous moral argument—a sign of living relevance rather than static sainthood.

Partition, Assassination, and Aftermath

India achieved independence in August 1947, but the joy was shadowed by Partition and the violence that followed.

Gandhi refused to celebrate; instead he walked among the wounded in Bengal and Delhi, fasting to still the knives.

On 30 January 1948, while on his way to a prayer meeting at Birla House in New Delhi, he was assassinated by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist who blamed Gandhi for what he saw as appeasement and betrayal. The nation mourned, and the world reflected on a life that had altered the course of political imagination.

In the decades since, civil-rights leaders, anti-apartheid organizers, and pro-democracy movements have adapted Gandhi’s techniques to their own struggles, proving the portability of his insights.

Books and Writings

Gandhi was an energetic writer. His journal “Young India,” later “Harijan,” became a platform for debate and instruction.

Among his most important works are “Hind Swaraj (Indian Home Rule),” a compact critique of modern civilization and a vision of self-rule;

“An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth,” a candid account of moral learning; and “Satyagraha in South Africa,” a narrative of resistance.

Smaller tracts such as “From Yeravda Mandir,” “Constructive Programme,” and “Key to Health” show his insistence that political freedom must be paired with personal and social renewal.

Reading Gandhi today, one encounters not only a historical actor but also a teacher intent on equipping ordinary people to act ethically in public life.

Legacy and Continuing Relevance

What makes Gandhi’s biography feel contemporary is less the specific colonial context and more the method he offers to divided societies.

He demonstrates how movements can combine moral clarity with strategic patience; how leaders can resist dehumanizing opponents while refusing passivity; how citizens can make politics a school of character. The method is demanding it asks for restraint, training, and a tolerance for slow victories but it has a track record of reshaping history without repeating its cruelties.

Gandhi’s legacy is not beyond criticism; it is precisely the friction of critique that keeps it useful.

As new generations confront ecological crises, digital misinformation, and democratic backsliding, the question is not whether Gandhi provides a ready-made answer but whether his practices truth-telling, nonviolent pressure, constructive work can be adapted imaginatively.

That, perhaps, is the best measure of a life well lived: it continues to offer tools.

Frequently Asked Questions (Short Reference)

- What does “satyagraha” mean in practice? It combines public disobedience of unjust laws with a commitment to nonviolence and personal discipline, aiming to convert opponents rather than destroy them.

• Why the emphasis on spinning? It symbolized economic self-reliance and criticized exploitative industry that undercut village livelihoods.

• Was Gandhi anti-modern? He criticized certain features of industrial modernity but embraced tools that served ethical ends public health, mass education, and accountable governance.

• How did he view leadership? As service. Authority, for Gandhi, arose from example, not command.

Coda: Reading Gandhi Today

To read Gandhi in the twenty-first century is to engage a demanding companion. He will ask you to consider whether ends can justify means, whether wealth without work or politics without principle can ever produce flourishing, and whether the dignity of opponents is a luxury or a necessity.

You may disagree with his answers. You may find his asceticism inconvenient or his compromises unsatisfying. Yet the convergence of moral seriousness and practical effectiveness in his life is rare.

That rarity explains why his vocabulary ahimsa, satyagraha, swaraj entered global speech and why his biography continues to guide citizen movements long after empires have changed their flags.

-

Biography3 months ago

Biography3 months agoMeet The Kalogeras Sisters: Biography, Age In Order, Parents, Ethnicity, Nationality, Social Handles, Fanfix

-

News7 months ago

News7 months agoCiroma to Uba Sani: You’re an epitome of good governance

-

Biography3 months ago

Biography3 months agoNoah Risling – Biography, Age, Wiki, Girlfriend, Ethnicity, Nationality

-

Biography2 months ago

Biography2 months agoGeorge Zinn — Wiki, Bio, Age, Family, Ethnicity, Nationality, Controversy

-

Biography3 months ago

Biography3 months agoAngel Unigwe Biography: Family, Net Worth, Age, Career, Boyfriend, Siblings

-

Biography3 months ago

Biography3 months agoDaisy Melanin Biography: Age, Career, Net Worth, Controversies, Boyfriend

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoBREAKING NEWS: Simon Ekpa Sentenced to Six Years in Finland for Terrorism and Tax Fraud

-

Biography3 months ago

Biography3 months agoGov. Uba Sani Biography: Family, Wife, Real Name, Career, Net Worth, Age 2025/26